By Felipe Lara, NYFA Game Design

How can you make your game more engaging and effective? In a nutshell, by making engagement stronger at the different levels of the experience and by making engagement connect to your ultimate goals: monetizing, teaching, or changing behavior.

There are three questions that can help you figure out how to best do that and they can be applied not only to games, but also to education, VR experiences, and other software that needs to engage users. Let me elaborate.

In this article we talked about how successful games and experiences share certain features. First, they stand out so that target players notice, then they connect with target players at an emotional level, so players are willing to give a few minutes of attention. Finally, successful games engage players and keep them for longer time, which in turn helps the game grow.

To do that, games can use different ingredients like compelling art, fun game mechanics, resonating themes, etc. Some ingredients (like art) are better at helping a game stand out, while others (like mechanics) are better at keeping engagement going. The challenge is how to mix and match these ingredients to take players to full long-term engagement.

Game design is an art and a craft that can take years to master, so I don’t want to oversimplify the art of engagement. That said, these three questions can often help you figure out what is missing and find possible solutions to make your game more successful at reaching your goals.

Question 1: Do You Have a Compelling Core Loop?

All games have a core set of activities that the player repeats over and over to advance through the game. These core repeatable activities are usually called loops. Clarifying and analyzing the core loop in your game can be very enlightening and can help you specify why your game works — or doesn’t.

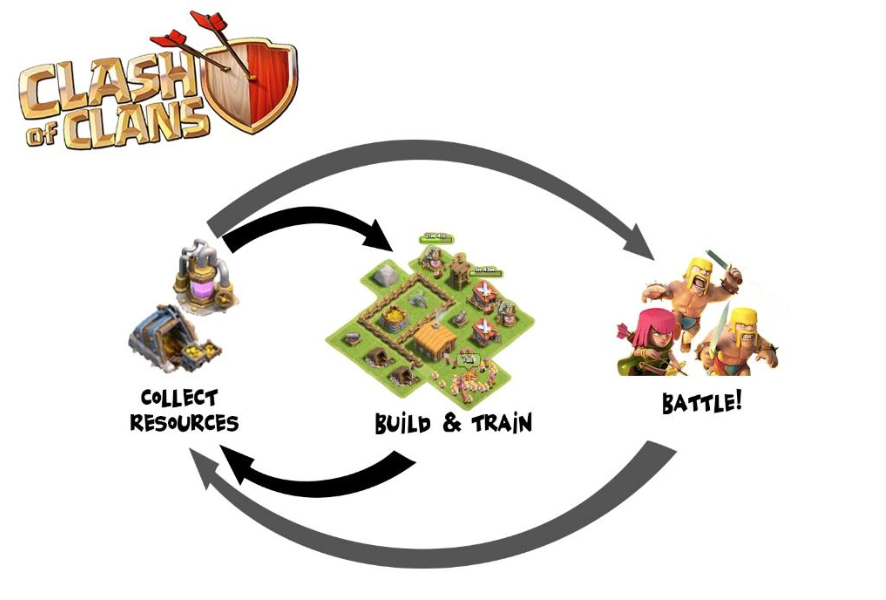

Games like “Clash of Clans” have perfected the use of loops to keep players engaged for a long time. At a basic level the loop is pretty simple:

You complete rewarding activities that compel you to come back and do more rewarding activities. Game designer and start-up consultant Amy Jo Kim identifies three rules that core loops need to follow to drive re-engagement:

- “They have a set of compelling activities. In “Clash of Clans” these activities are all related to building up your village and battling other villages.

- “Those activities give you positive feedback that make the completion of activities much more satisfying. This feedback makes you feel that you are getting better at something, and getting rewarded for it. In “Clash of Clans,” as your village grows and as you defeat other villages you get access to more resources and better troops.

- “Built into this cycle there are triggers and incentives to keep you going back to the game. In “Clash of Clans” all the building up, collecting resources, and troop training takes time, so there is an incentive to keep coming back to reap the benefits of what you have already done. Also, as you put more time into developing and customizing your village and improving your troops, you feel more invested in the experience, which makes you want to go back again.”

Amy Jo Kim’s analysis is very useful and provides interesting sub-questions to help identify potential problems and opportunities with your core activity loop:

- “Are the activities in your core loop compelling enough? How can you make them more compelling?

- “Are you giving your players enough positive feedback about the activities they completed? Do they feel they are progressing and mastering a new skill? How can you amplify that positive feedback?

- “Does your loop have triggers that pull players back into the game? As they go through the loop, do players feel more invested in the game? Can something be added to lure players back? Can something be added to make players feel more invested?”

If you want to go a little deeper on how these 3 rules work in different loops, take a look Amy Jo Kim’s full article here.

Question 2: Is Your Core Loop Tightly Connected to Your Goals?

Connecting your core activity loop tightly to your goals is key to making a successful game. There are many for-profit, free-to-play games that don’t sell enough items to be sustainable, and many educational games that are not very good at teaching what they were suppose to teach. Some of these games are even fun, using proven fun mechanics copied from other successful games, but still, they are unsuccessful at connecting those mechanics to their goals in any meaningful way.

If you are trying to sell items, those items should enhance your core loop experience.

A successful example of connecting your loop to your goals is “Pokemon Go.” In “Pokemon Go” your beginner core activities are basically three:

- Walking around searching for Pokemon.

- Catching the Pokemon you find by throwing PokeBalls at them.

- Walking to PokeStops to get more PokeBalls and other items that will make it easier to catch Pokemons.

At first you have enough PokeBalls and catching Pokemons is very easy, but as you level up you will find it harder to catch Pokemons. You will need many more PokeBalls and will run out of your supply faster. You can always walk to a PokeStop and get more PokeBalls, but since you are already somewhat invested, spending $1 to get extra PokeBalls doesn’t sound bad. You could keep playing for free by continue walking around to different PokeStops, but by spending $1 here and there you can make your play much more convenient and increase your chances of catching rare Pokemon faster. The items that you can buy directly make your core loop easier, so even if the game does not force you to buy anything, many players end up spending a few dollars here and there to improve their experience.

In the case of an educational game, the set of core activities should produce learning. In her article “Why Games Don’t Teach,” Ruth Colvin Clark talks about some examples where the game activities do not align with the educational objectives — which makes the games very ineffective.

Clarke presents some experimental evidence that concludes that narrative educational games lead to poorer learning and take longer to complete than simply displaying the lesson contents in a slide presentation.

One of the games she tested is a game called “Cache 17,” an adventure game designed to teach how electromagnetic devices work. The problem with this game and the other games she mentions in her study is that core loops are only vaguely related to the topics they are supposed to teach. In the case of “Cache 17,” the players need to solve a mystery about some missing paintings that disappeared during World War II by searching through an underground bunker. The link to the topic is that players occasionally need to build an electromechanical device to open some doors and vaults in the bunker. The core loop is about exploring a bunker and finding clues, not about experimenting with electromechanical devices.

Not surprisingly, Clarke’s study found that reading a slide about electromagnetic principles was quicker and much more effective at teaching the topic than playing the game.

When the educational objectives are more aligned to the core loop the results are very different. Using a resource strategy game like Sid Meier’s “Civilization” as a supporting tool to teach the relationships between military, technological, political, and socioeconomic development has been so successful for educators that a purely educational version of the game was announced for 2017. Here, the core loop is closely aligned to the educational objectives: The core play is all about figuring out the right combinations economic development, exploration, government, diplomacy, and military conquest to create a successful civilization.

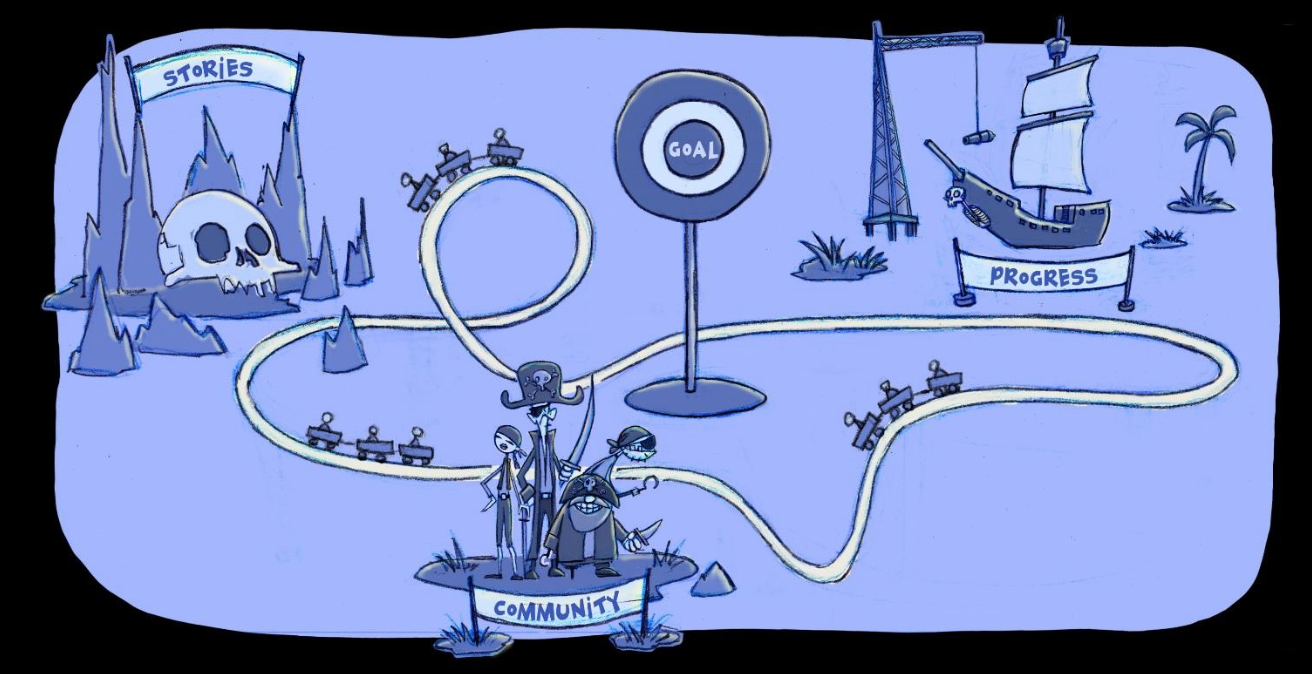

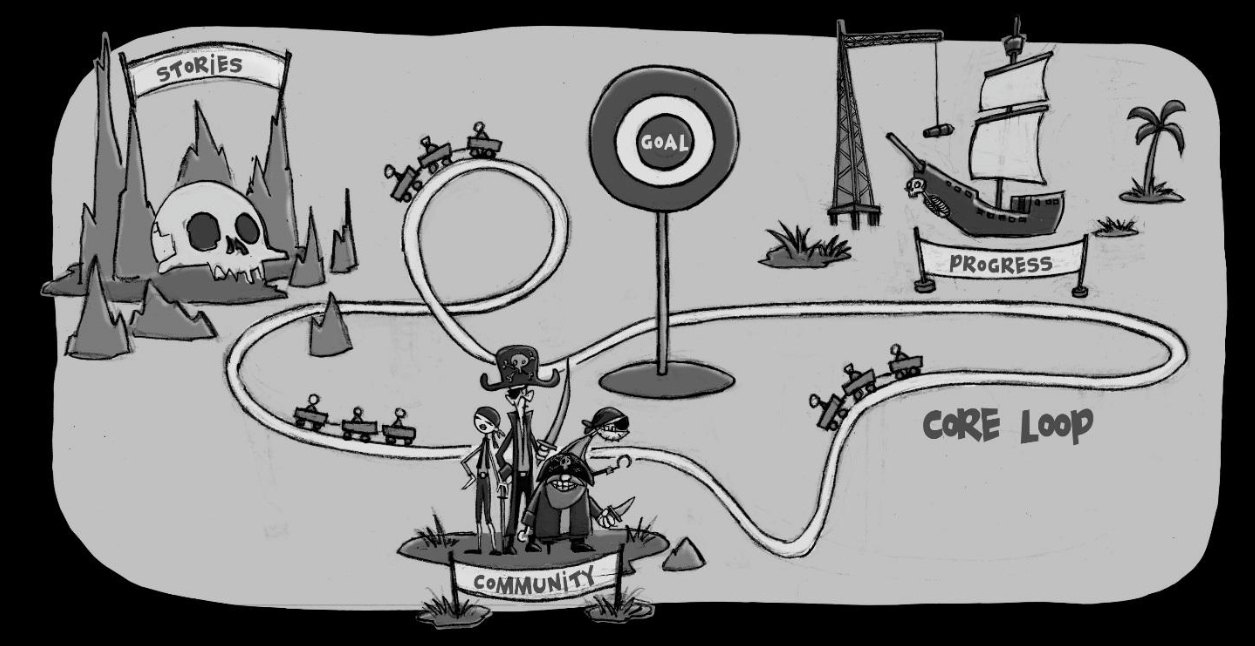

Question 3: Is Your Core Loop Connected to All the Ingredients of an Engaging Experience?

The ingredients of engagement go beyond game mechanics; they include other things like art, theme, story, and community building. When you are able to connect your loop to these other ingredients the engagement is much more powerful.

For example, “Toontown Online” is a game developed by Disney. It’s overall goal was to defend a cartoony world from invading business robots. Designers wanted to make sure that the core loop reinforced the overall theme of the game. This theme was something like: “Work is always trying to take over our play time, but play most prevail.” So, the need to play was built in as an essential part of the core loop.

Without playing arcade-like mini-games, “Toontown Online” players could not earn jelly beans — the main currency that was essential to buy gags that would help players stop the business robot invasion. So even when the story and main conflict was about defending Toontown and battling business robots, players couldn’t do it without playing and having care-free fun. The result was a core game loop that reinforced the theme of the game: The conflict between work and play. Because the theme resonated with many players beyond the original target audience (kids ages 6 to 12), the game ended up being very popular with players well beyond the target demographic.

As players repeated the loop, the game prompted them to explore other parts of the world, team up with other players and make friends, and unfold new stories. In other words, the loop pushed players to discover new art and stories, build community, and master the mechanics, which made the game much more engaging. The result was an average player lifespan much higher than most other family-oriented games at the time, which made the game very profitable for over 10 years.

The more you are able to connect your core loop of activities to the ingredients that make a game engaging, the stronger and longer engagement you will have.

Conclusion

Your core activity loop is a powerful tool to make your game or experience more engaging. Once you clarify your loop, these three sets of questions will help you shortcomings and opportunities to make your game more engaging and successful:

- Are the activities in your loop compelling enough? Do you provide enough positive feedback when players complete the activities? As players complete a loop do they get something that makes them feel invested?

- Is the loop directly linked to your objectives? If you are selling something, does that make the loop more satisfying? If you are teaching something are the core activities directly linked to the topics the player needs to learn?

- Does your loop reinforce the different ingredients of an engaging experience? As players go through the loop, can you provide more things to discover and get mesmerized by? Can you add more interesting pieces of a story? Can you guide the player into forming a tighter community?

Do these questions trigger for you new ideas on how to improve the game you are working on? Let us know in the comments below! And, if you’re ready to learn more about game design, check out NYFA’s game design programs.