New York Film Academy (NYFA) Documentary Film student Richard Brookshire recently wrote an article for New York Times Magazine about his experience serving in the army as a Black, queer man, joining the Black Lives Matter movement, and what he has been doing to bring Black stories to life as a filmmaker and a storyteller.

NYFA reached out to Brookshire to continue the conversation from his New York Times Magazine article and to discuss his experience as a Black documentary filmmaker, his upcoming short film Boukman’s Prayer 2.0, and the future of Black stories in the entertainment industry.

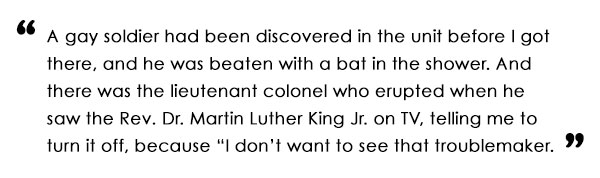

Before pursuing filmmaking, Richard Brookshire served as a combat medic with the 170th Infantry Brigade in Germany, and later Afghanistan. At this time, Brookshire recalls his closeted sexuality due to the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, and also remembers being one of a few Black soldiers in his 40 person platoon. In his article for New York Times Magazine, Brookshire wrote:

Through Brookshire’s personal encounters, the experiences of his loved ones, and witnessing modern events of racial inequality unfold (like the horrific shooting of Trayvon Martin), led Brookshire to join the New York chapter of Black Lives Matter and to co-found the Black Veterans Project, a racial equity and archive initiative created to shed light on systemic racial inequities within the U.S military (both historic and present).

Brookshire’s interest in racial injustice led also opened up another area of interest; film. “I recognized how the medium of [documentary] film was the perfect space to merge my background and skill set to capture Black American life for future generations.”

“Film is one of the most powerful forms of propaganda we have in retelling histories and cultivating a public imagination around how we see ourselves as a society and our shared humanity,” says Brookshire. “Just as it can do harm, it can also harness good. It can expand our collective understandings, give us a window into lives far different than our own, and equip stakeholders and activists with powerful narratives to drive necessary and provocative awakenings around injustices across societies.”

After Brookshire’s four year old niece passed away last year, he says it was the motivation he needed to study the documentary filmmaking craft. “NYFA felt like the perfect place to gain expertise from leading filmmakers in an intimate intensive program geared toward teaching me the fundamentals,” says Brookshire. “I credit NYFA alum, Clyde Gunter for persuading me on what NYFA had to offer.”

Brookshire notes that documentary filmmaking can change or broaden an individual’s perspective. “It only takes one mind to begin planting the seeds of change and revolution. We are in constant evolution as human beings, and we must not shy away from harnessing the power we have to inspire each other to do better, to be better and to create new systems that reflect a reality that is informed by the shared understanding of our common humanity.”

As a filmmaker and activist, Brookshire turns to creators like Spike Lee and Henry Louis Gates for imagination, creativity, and unforgettable storytelling. “I always joke with my friends that if Spike Lee and Henry Louis Gates had a director baby, it’d be me.” He notes that Spike Lee has always taken incredible care and consideration “in capturing the splendor and hardship of Black American Life.” As for Henry Louis Gates, Brookshire claims Gates “has created unparalleled works that dive deep into the overlooked African American histories.”

For his next project, Brookshire tells NYFA that his short film Boukman’s Prayer 2.0 will explore “five Black artists surviving the COVID-19 crisis in the days leading up to the riots.” In his essay film, Brookshire describes it as an exploration of “Black folk who find freedom within and access planes in their creative imagination to allow a spiritual awakening and healing outside of an anti-Black society.”

While the country continues to address various systemic racial prejudices and injustices, the entertainment industry has its own work to do too. “The archive is full of Black histories and Black life to tell. The diaspora is rife with untold and unexplored characters and circumstances,” says Brookshire. “If we are to bridge the long-standing racial divide, we must create spaces for Black stories to exist, and not just those that retell Black traumas (which has been a primary avenue for Black filmmakers write large).”

He continues to note the importance of Black documentaries and their ability to show “the vastness of our humanity and experience,” and urges the conversation of ownership with Black storytelling; “who owns Black stories is just as important as who tells them.”

In addition, Brookshire shares that mentorship cannot be overlooked either. “Sharing resources and knowledge creates pathways to opportunity,” he says. “The reason the canon of documentaries is lacking relative to Black stories is because, for far too long, film was an exclusive space and, in many ways, it still is quite a privilege to be able to do this sort of work.”

New York FIlm Academy would like to thank Richard Brookshire for continuing to share his stories and insight as a Black filmmaker and encourages everyone to read his New York Times Magazine article and to be on the lookout for his upcoming short Boukman’s Prayer 2.0.